Representing Chicago’s First Black Mayor

By: Tam, 2005

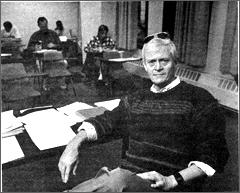

Americans identify with Chicago as the city of giant shoulders and not so modestly, the city that works. Naturally, like any other prominent metropolitan area, a majority of Chicago was built on the ideas of migrants. Men like Alton Miller, who served a lifetime in politics and civil service in the war of loyalty.

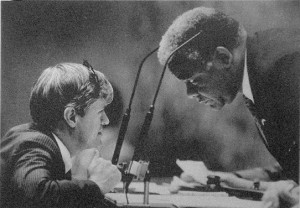

Originally, Miller worked as managing director for five-years at the Washington Ballet eventually relocating to the Chicago City Ballet as the general director in 1983. A year later Miller met Chicago’s first black mayor, Harold Washington, through the city’s private sector resource council. The council connected outside professional advisors into networks for major city offices. At the time, the mayor was seeking a press secretary after coming out ahead of Richard M. Daley and Jane Byrne during the 1983 Chicago elections.

When Mayor Washington asked Miller why a ballet manager should represent the mayor of Chicago, Miller appealed on how PR type management for any entity, especially politics, would be beneficial to him. “It’s the most focused work you could do. Everything counts precisely backwards,” said Miller.

Miller attributes his interest in politics to growing up with parents working in the Pentagon. Before living in Chicago, Miller and his family were active members of the Democratic Party in D.C.. He grew up believing to leave the government alone without direction is irresponsible. However, throwing everything out and beginning with a new white-collar corporate influence is incorrect too. In 1984 Miller took a political step and won his position as Harold Washington’s advisor.

During his four years, Washington needed to gain absolute control of his office through a majority vote of 30 council members, but lacked total support. This struggle, ultimately known as “the Council Wars,” took place due to powerful opposition. Miller said he and Washington were constantly at odds with three prominent aldermen, Eddie Vrdolyak, Eddie Burke and Ed Kelly whom came to be known to the mayor and his supporters as, “the Eddies.”

“This was a city that was designed to confine blacks into a narrow corridor, ” explained Miller.

Aldermen Vrdolyak brought 28 new white members to the council and struck down every issue purported by the black mayor. Some important issues Washington fought “the Eddies” on included city budget and federal grants. At that time, Chicago’s budget was unbalanced and predominately concentrated into prominent neighborhoods. Up until Mayor Washington’s office, city money had been spent on $300,000 PR contracts through big business camaraderie, said Miller. Partnerships like that of the First Bank of Chicago and R.M. Daley proved to be unjustified upon further investigation. The lack of concern for the issues from the top political executives concerned the mayor. His influence became a threat to any previous cozy arrangements.

The Community Development Block Grants were Reagan’s version of support for major U.S. cities. The grants were money that was meant for viable improvements like gutters and streetlights for the entire Chicago area including neighborhoods and business districts. According to Miller, Chicago received 300 million dollars that turned into a slush fund for Daley and Byrne’s administration.

Despite the uphill battle, Mayor Washington sought to improve the quality of life for everyone including the poor and black. “This was a city that was designed to confine blacks into a narrow corridor, ” explained Miller. The buildings were built narrow and upward on purpose. A mother would have no way to watch her children playing outside on the ground from the 17th floor. The people of poor neighborhoods were consolidated to save space and money. Mayor Washington was credited for being fairer on equal rights then any politician of the time. “He brought more women into the city office then anyone had ever,” said Miller.

“I can deal with your enemies but you’re going to have to protect me from your friends.”

Beside “the Eddies” and countering media biased slander, Miller also had to fight with the backlight groups that wanted to represent the mayor. Groups that pressured Miller because they thought he wasn’t packaged correctly. He was forced to defend his efforts and told them Mayor Washington didn’t need to be packaged because his character was strong enough to stand itself. Miller told Mayor Washington, “I can deal with your enemies but you’re going to have to protect me from your friends.”

Miller says that the greatest thing he learned from serving Washington was that there is a difference between leadership and bosses. As an individual we are helpless but in civic institutions you are at your greatest power.

Some of Alton Miller’s life achievements include service in the Marine Reserves, consultant to Philadelphia Mayor Goode, communications director for Carol Moseley-Braun, campaign manager and consultant throughout Miriam Santos’s career, and published author. Currently Miller represents the advocacy efforts for the Illinois Arts Alliance, and occasionally writes articles for thecommongood.org. He is also a fulltime instructor at the media school in Chicago Columbia College.